K-State’s Butler Digitization Lab brings historical archives to life using modern digital magic

When Irina Rogova comes into work each day, she never knows what intriguing, surprising

or even strange tidbit of history she’s going to uncover in the K-State archives.

Maybe it’s an ad from the 1980s for a K-State grandfather clock. A script for a skit

from a College of Health and Human Sciences “Hospitality Day” event. A cookbook from

1783 in pristine condition that provides a window into how people lived (and ate!)

in the past. Or even a scrapbook from an army veterinarian’s travels before serving

during World War II.

Rogova is an assistant professor and digital resources archivist in K-State Libraries’

Richard L. D. and Marjorie J. Morse Department of Special Collections. She operates

the Butler Digitization Lab and her mission is to digitally preserve K-State’s vast

collection of archives and make these materials more accessible to the public.

“There’s an idea that the archive is very serious, and we sit in our reading room

and we have to be very quiet, and it’s a serious academic endeavor,” she said. “But

the archive exists because people are emotional beings. We are nostalgic, and we want

to save things. I would love to see more archives embrace a more dynamic way of looking

at our collections.”

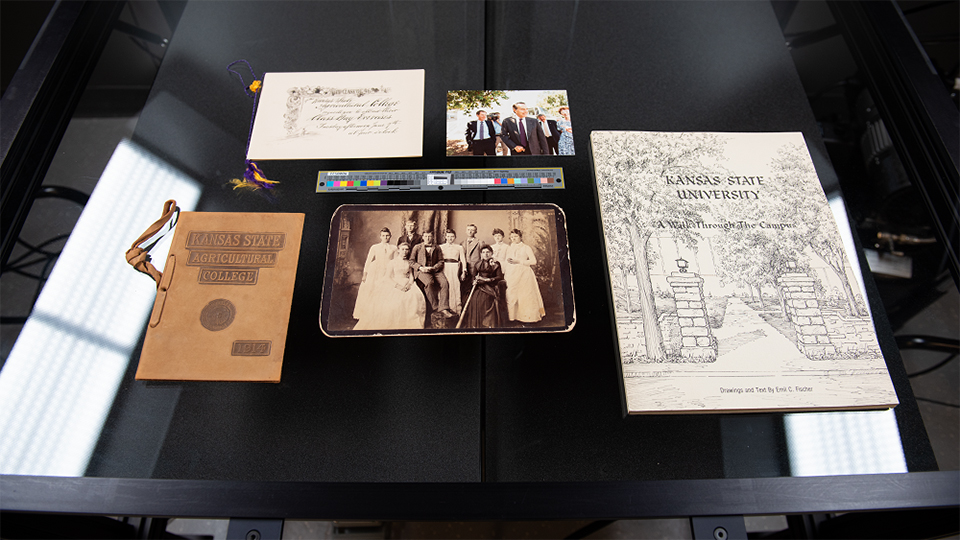

The Butler Digitization Lab was established in 2021 thanks to a gift from the Butler

Family Community Foundation, and has two primary purposes. The first is easy to guess:

digitizing historical materials from the university’s archives (like the ones referenced

above) and making them available online to a worldwide audience. However, people may

not realize that an equally important function of the lab is archiving current digital

material produced by the university, such as emails, newsletters, websites, Instagram

posts, etc., and preserving that record for future generations.

“People have this idea that, ‘Oh, it’s digital — it will last forever,’” Rogova said.

“There are certainly aspects of that that are true, but there’s also definitely a

very delicate aspect to these materials, especially at the rate that technology evolves

now. There’s a whole different process to archive and preserve digital materials than

there is with physical materials.”

Media storage devices become obsolete very quickly — remember floppy disks, Zip drives,

and those optical discs you’d insert into your computer? K-State archivists are able

to use special digital forensics computer technology — originally developed for law

enforcement — that allows researchers to view obsolete digital media without changing

it.

“We want to make sure that we’re maintaining that authenticity with those digital

files,” Rogova said.

Since the university is a state institution, K-State is legally required to maintain

certain records that must be properly processed and preserved for future access. The

lab also uses an online service to crawl public-facing websites searching for relevant

information to archive regarding the university, student organizations, faculty and

staff, and even Kansas life and culture.

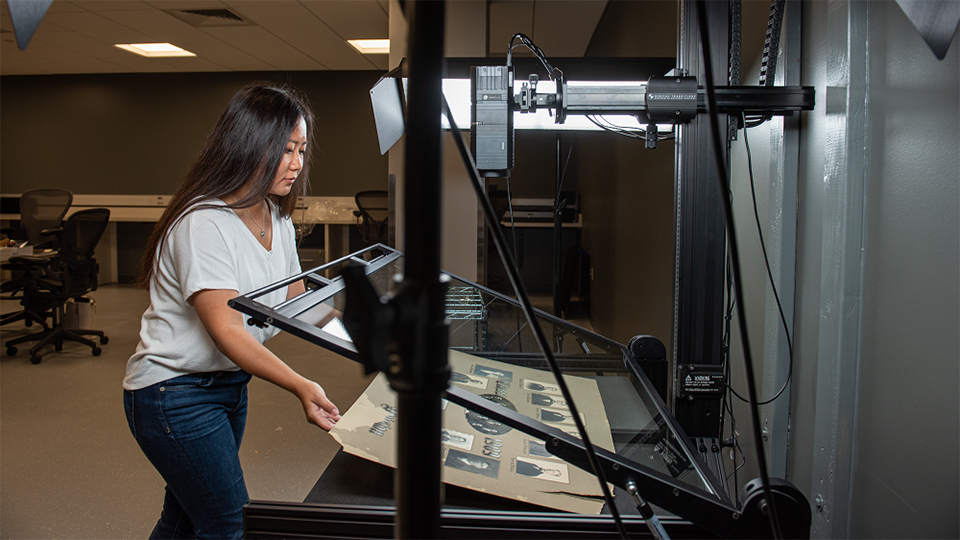

For historical materials, the lab has state-of-the-art digitization equipment, including

high-quality digital cameras that produce clean, crisp, high-resolution images of

printed items. The lab also has a book cradle for digitizing materials with tighter

binding and an accompanying software program that collates these scanned pages.

One of the lab’s current major projects is sorting through a huge photo collection

— about 30,000 images — put together by past K-State archivists organized by subject

and person (for example: Anderson Hall). The lab digitizes the university’s Royal Purple yearbook, and is even working on digitizing the K-State Alumni Association’s own

K-Stater member magazine, dating back to 1951.

“I’ve seen many, many years of the K-Stater,” Rogova said with a chuckle. “It’s interesting to see what the magazine thought

was important for their alumni to know during certain time periods, what they covered,

who was on the covers, stuff like that.”

Rogova said people sometimes have the misconception that digitization is an instant,

easy process where content can be quickly uploaded and searched for on the Internet.

They don’t always understand the amount of human labor and quality control that goes

into the process of digital archiving.

Digitizing every piece of media ever produced by the university would be impractical,

and archivists must prioritize what would be most valuable and of the broadest appeal

to a general audience.

Archived material should have a date, brief description and copyright information

attached — a process that can’t be automated. As an archivist, it’s also important

to examine your own bias when describing a photo, Rogova said, especially when there

is little historical info to accompany the image.

Other challenges include how to archive and flag materials that may be difficult to

look at, with violent, racist or potentially offensive content.

“Balancing that inclusive language with accessibility is something that we’ve worked

on,” Rogova said. “It’s exciting for me to be in a profession that is constantly re-evaluating

its relationship to the archival record. What are we doing to combat our biases, what

are we doing to continually educate ourselves, to continually diversify the sources

of not just our collections but also our policy-making, to make sure that our collections

are inclusive and equitable and capture the most holistic human experience possible.”

Rogova also values recording oral history — allowing people to provide a first-person

account in their own words.

“Hearing from the person their own experience of it, especially with that ability

to reflect on 10, 20, 30, 70 years of their life, is a really special experience,”

she said.

People tend to think of “history” as the past, but what’s happening on campus now

will be regarded as history one day. Rogova said it’s important to preserve that information,

so that future generations can have context for events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If we’re not actively seeking out those materials of our current history, we’re gonna

have just as many gaps in the archive as we have for materials that are 100+ years

old,” she said. “It takes a lot of people to make an archive, if you want to have

a record for the future.”

Additional resources

-

View the Libraries’ digital archives: https://lib.k-state.edu/research-find/digital-archives/

-

Take a video tour of the lab: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYMTXW-PJ2U

-

If you’re a K-Stater and have an item you think might be of interest to the K-State archives, contact: libsc@k-state.edu “We see value in pretty much everything,” Rogova says.